By Tony Tremblay

Originally published in: Bibliography of New Brunswick Bibliographies & Accompanying Essays. Kentville, NS: Gaspereau Press, 2020. An earlier version of this paper was delivered at the New Brunswick Bibliography Symposium (Fredericton, 2019).

I began my talk (and shall begin this written version) with the kind of news story that most New Brunswickers now recognize as not just normal but normalized. It is excerpted from a 22 September 2018 editorial in the Fredericton Daily Gleaner, a date just two days before the last provincial election. The editorial is titled “Turn Around Troubled Fiscal Ship.” I’ve placed the salient lines in italic type:

Let’s think about children born in New Brunswick today.… There are many problems here that will put them behind compared to other Canadians and, ultimately, make it more difficult to stay here when they grow up....

Overall, New Brunswick has the lowest median income in Canada—$59,347 in the last census, compared to a national average of $70,336. It’s as sure a sign as any that the province is falling behind the rest.

The province also struggles with literacy: With about half of adults being functionally illiterate, many of these children may be born into households where one or both parents cannot read or write well. This will put their families at an economic disadvantage; and unfortunately, it’s no guarantee children will attain reading and math proficiency in public school.

To boot, they will inherit a significant burden of debt accumulated by previous generations. From 1998 to 2017, the province’s net debt increased 68 per cent, even adjusting for inflation. If the same trend continues, the provincial debt will be more than $23 billion when they reach adulthood. (A10)

Those are sobering words indeed — and, as we are carefully coached, we should put them at the forefront of our agendas. Indeed, many of us have. But, as one of my very good students said in class recently about similar statements, “How are we to proceed from that knowledge?” Her question, of course, is exactly right. How are we to proceed from such pronouncements and, to invoke the theme of the symposium, how do we consider those statements relative to our own embarkations into curiosity-driven scholarly work?

To be an intellectual worker in New Brunswick at this moment in time is to take that question very seriously. In fact, I think the consideration of the conditions within which we embark is the most pressing consideration that faces us today. And because of that importance, I will rephrase the question slightly to capture what the question actually is — as an English professor, I must always be attentive to clear language! Here, then, is what I think the question is (and, so, the question we should be asking ourselves): How are we to proceed with our intellectual work in the midst of a relentless public media lobby that, in seeking accommodation for pipelines, natural gas fracking, and a host of other industrial concessions, has completely normalized the idea of our province’s deficiencies?

Ask anyone who has been paying attention to provincial affairs in the last ten years and they’ll say the same thing: as a province, we are broke, hopelessly dependent on wealth transfers, and about to “fall off the cliff.” Indeed, “falling off the cliff” has become something of a neoliberal provincial mantra. We have lobsters, fiddleheads, lupins, and now “falling off the cliff.”

In recasting my student’s very smart question in this way I do not mean to begin negatively — or, worse, flippantly. But I do wish to emphasize that our various embarkations into cultural and intellectual work, whether driven by social expediencies or curiosity, are increasingly occurring in an environment of austerity, utilitarianism, suspicion of intellectual workers, and, if I may be so bold, calculated disregard for a public commons in service of private commercial ends. That’s not meant to trade provocatively in the sleeve-worn conspiracy theories that abound in places of uneven development, but only to capture, in direct language, a message about our province that bombards us daily.

What I will do below is reconstruct my own process of embarkation in that context, hoping to illustrate where we all can find openings and opportunities in the current provincial and national environments. My great wish since beginning my work is that we might be able to construct a different set of narratives about what New Brunswick is and can be.

It is that hope, of course, that compels us all to do the kind of work we do. And so the first thing of consequence that I wish to say is that we should begin thinking of ourselves, if we don’t already, as activists. Not just cultural workers, but activist cultural workers. The environment we work in demands nothing less.

Indeed, if we are to operationalize our work within the kind of messaging frame I just described, then we must think of ourselves as not just occupying but also claiming the periphery on which we’ve been placed, for while the New Brunswick polity is not openly hostile to what we do, neither is it especially receptive, having hospital waiting times to reduce, accumulated debt to pay down, and an energy corridor to build. A digital collection of the letters of the mid-century modernists is well down its list.

What also helps is to understand the nature of what I think of as our multiply deferred pluralities. We are humanists not only in a larger galaxy of entrepreneurs, financiers, and capitalists, but also humanists in a very small province in a constellation of other, mostly larger, provinces and regions. And therein is the challenge. If, as a country, we cannot easily ship our products across provincial borders, or, as a region, find common ground in shared governance, or, as a province, bridge the solitudes of French and English, then how, but as activists, are we ever going to win attention for our non-essential, often curiosity-driven work? Like it or not, we are endeavouring to assert ourselves in a comparatively small, economically weak, and politically insignificant province whose most vocal narrators have convinced the population that wood, oil, gas, and energy carriage are our best bets for a sustainable future.

But do not despair. In pointing out the obvious, I am not being negative. Rather, I am suggesting that these conditions provide a productive space in which to do our work. We need only consider the opportunities embedded in our Canadian federation as it is constituted.

The existence of that particular multiply deferred plurality—the fact that Canada is one entity made up of many parts—should reveal to us that the ascendancy of particular parts of our widespread federation has changed over time. In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, New Brunswick was at the forefront of Canadian culture. The province’s early writers were considered to be some of the most consequential in British North America, and, once Canada became an independent nation, New Brunswick writers were the first in the country to formulate what a national accent — a uniquely “Canadian” accent — was. As the country expanded westward, that sense of a trail-blazing literary excellence changed, as of course it had to. It could not have been otherwise.

As our province began to suffer economically, so did the narrative of New Brunswick change, taking us conceptually from a place where hope had been restored (I’m referencing the Loyalist motto there and the larger Loyalist promise) to a place where it had been lost. The further New Brunswick became from central and then western growth poles of economic vibrancy, the more the narratives darkened. All of which gives me great optimism, for it suggests, first, that culture is a construction that has political dimension, and, second, that culture moves. It is restless and peripatetic, never content to stay in one place. Cultural authority in Canada, then, has always been on the move and always been coaxed into vibrancy, having had heydays in Halifax, Montreal, Fredericton, Ottawa, Montreal (again), Toronto, Vancouver, Toronto (again), etc. New Brunswick is due for a return visit!

Let me be even blunter about what I see as the fertile ground for our work in a seemingly less-than-accepting utilitarian environment. When I started my ten-year term as a Canada Research Chair in New Brunswick Studies in 2007, I began by making a careful study of what, from my sectoral vantage point, was missing. Here’s what I found: New Brunswick had no dedicated provincial publisher, no provincial encyclopedia, no provincial critical journal, no comprehensive written history (it still doesn’t), and no province-specific curriculum. Moreover, the grassroots talk radio and free press traditions that had earlier flourished had become very weak; there was almost no English-language documentary film industry or historical fiction in the province; and the last comprehensive scholarly book on New Brunswick literature had been published twenty-five years earlier. Not only did something have to be done, but the glaring absences provided a very clear road map for how to proceed. And I knew, as well, that I must start quickly, for the direct result of the absence of those essential knowledge resources was that other people were defining, for their own purposes, what New Brunswick was and should be. Those narrators were increasingly attaching the term “beggarly” to the province, footnoting any sense of achievement to history and attributing current success to the “miracles” (their language) of great men such as Frank McKenna and Francis McGuire. Increasingly, the narrations of the province were homogenizing history, identity, and fate: New Brunswick, those narrations said, was empty of what was essential, namely, spirit and drive.

And so I took my cues from that, concluding that achievement could as easily apply to the social and cultural as to the corporate and industrial. This was the first of many openings. Calls for entrepreneurial acumen, in other words, could be interpreted more broadly as calls for intellectual work. There was ample room—and, indeed, a clear need—to work against narrative consensus by embracing the very subtexts of that consensus in activist terms.

But how does one do so? How does one operationalize a culturally activist agenda?

Theoretical Foundations

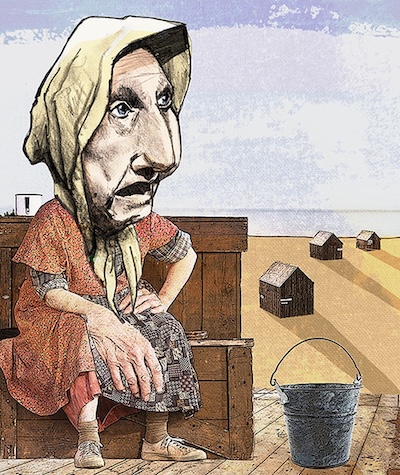

In thinking through that question, I revisited a suggestion that resides at the heart of historian Ian McKay’s still-relevant Quest of the Folk. That book explores how a small group of cultural producers in Nova Scotia enacted a practice of anti-modern nostalgia to narrow the province to a few fixed but culturally resonant categories, categories that championed what was folksy, rural, and innocently, often charmingly, backward. The power of that stereotyping, observed McKay, was its difference from a modern urbanism in central Canada that was frenetic and thus always unstable. Cultural workers in the Maritimes turned that difference to advantage by popularizing narratives of quiet, calm, and ease that attracted harried urbanites who sought escape from the dehumanizing speed of their cities. McKay’s study, then, showed how an entire region of the country was both constructed and represented in literature, heritage, tourism, and social science. Today, one need only consider the ads for Newfoundland or PEI tourism to see how this representation works. [Figure 1.] The scenes depicted are visually stunning, the colours warm—and the people virtually absent. The only humans present are children, preferably red-haired and freckled. Clothes flap in the breeze on a homemade line. No paved roads are ever visible. Only fog, fiord, and edge; indeed, the very vineyard of the Lord.

The resonant point that McKay’s book makes is that this “powerful form of hegemonic ideology”—namely, the appealing persuasions of folk representation—affords a unique opportunity “for creative cultural opposition” (308, italics added). What McKay invites is opposition to popular forms of representation and, as importantly, creation of new ones. Specifically, he challenges us as intellectual workers to look beyond stereotypes in order to construct “new ways [of] arriving at new mythologies” (153).

Now, it is worth pointing out here that that is exactly what the promoters of New Brunswick’s new economy want: they, too, want history stripped of the stereotypes of dependency and want. They, too, want renewal via creation, which they define in entrepreneurial language. That alignment of interests cannot be bad for us, but it does require us to present our work in ways that foreground its provincial utility, something, I realize, that will not sit well or easily with everyone. It didn’t sit well or easily for me, this necessity of finding common points of intersection with the corporate classes, until I realized that the poetics of new creations, whether cultural or industrial, place equal demands of relevance on all of us—and similar challenges.

For cultural and corporate workers alike, inviting new creations and myths in an alleged backwater like New Brunswick quickly reveals how tilted the ideological landscape is against our interests. The powerlessness that ensues from that tilting—from the presumption of our folksy backwardness or hapless dependency—is best summed up by Acadian writer Antonine Maillet’s famous washerwoman, la Sagouine, who says, under similar conditions of a contradictory freedom, that it “ain’t easy earnin yer living when you ain’t got a country of your own, ’n when you can’t tell yer nationality.… Cause you end up not knowin what the hell you are” (La Sagouine 166). [Figure 2.] In other words, renewal becomes very difficult when the power to define oneself is largely out of one’s hands. Here, then, is another opening to the work we do in heritage, identity, language, etc.

What Maillet’s washerwoman, McKay’s theorizing, and narrators of an Energy East dream express clearly is that breaking stereotypes can only ever exist within larger ecologies of story, whether a modernist story system that seeks order and authenticity through history, thus making negative presumptions about us, or a postmodern story system that revels in disorder and contradiction, thus rendering us rather absurd. Under both those systems, self-definition and renewal, while not impossible, are always slightly out of reach.

I theorize our work in New Brunswick in this way to make the larger point that la Sagouine’s, McKay’s, and the Irving dreamers’ conundrum is common — and also very much our own. The task facing all of us is equally absurd: how do we re-imagine our province of New Brunswick in a post-national era, an era characterized by skepticism, discontinuity, and deracination, not to mention a robust suspicion of place-based identity politics? The task seems patently anachronistic and, in the minds of some, confines those of us who embark on such projects to the realms of the romantic, the conservative, or, worse, the tribal. Surely this is the problem that Irish poet Seamus Heaney identified when he said,

Even if we have learned to be rightly and deeply fearful of elevating the cultural forms and conservatisms of any nation into normative and exclusivist systems, even if we have terrible proof that pride in … [one’s] heritage can quickly degrade into the fascistic, our vigilance on that score should not displace our love and trust in the good of the indigenous per se. On the contrary, a trust in the staying power and travel-worthiness of such good should encourage us to credit the possibility of a world where respect for the validity of every tradition will issue in the creation and maintenance of a salubrious political space. (460)

I raise that tension between the hopes for renewal and the realities of narrative and ideological power because it governs the ways in which we, too, as intellectual workers, push off into a future of finding new ways of studying and representing the worlds from which we come.

It is worth noting that this challenge, while not solely Canadian, is certainly characteristically so, for it is a feature of both our colonial history, which cast the people of Canada as rubes (second-rate colonial subjects at best), and our experiment with distributed federalism, which constructs the peripheries of Canada in deliberate ways that reinforce qualities of the centre.

To understand how the first group of homegrown Canadianists saw this problem of balancing the local with the national, we have to go back to 1943. When E.K. Brown in that year lamented the regionalist phase through which Canadian literature was passing, he consoled himself with the thought that that stage was a necessary “purgation” that would only slightly delay the “coming of great books” (25). For him, localism was akin to adolescence on the road to national maturity, much as rurality was an economic phase on the way to urbanism.

In arbitrarily dividing “native” and “cosmopolitan” writers (338), thus putting the poets of the soil (“the old masters,” as he called them) into a secondary category, A.J.M. Smith, in The Book of Canadian Poetry, did much the same thing as Brown: that is, he allowed us our uniqueness, but only as concession. New Brunswick could only be New Brunswick, he argued, in the larger context of Canada—and Canada likewise in the larger commonwealths of Europe or the Americas. The narrower the division, both Smith and Brown implied, the more un-literary the expression. Their point was clear: What we are most fully could only be expressed as a footnote to a larger authority. Not only were Canadian and New Brunswick identities contingent, then, but, in our most intimate surroundings (our languages, our places, our thoughts), we were incomplete. That was the baseline.

If we move ahead just one generation, we see those prejudices start to collapse—and that is exactly what I want to illustrate as a model for our hopefulness, a model of how culture, however narrow, can be coaxed into authority.

For pioneering Atlantic-Canadian literary critic Terry Whalen, this denial of the empirical for the abstract (the denial of place for nation, cradle for gun) was actually productive because it defined the starting point of one’s cultural activism. In other words, said Whalen, we need the baseline. “Provincialism,” he said, that which is “alert to roots, open to the wider world, [and] creatively curious is valuable [because it] provides the only solid basis for a larger … understanding [that] stands as an alternative to that kind of national unity that is merely a bolting together” (33). For Whalen, the only means of our escape from “colonialism” is thus “a [calculated] neo-provincialism,” which he defines as “a new faith in home … which trusts the cultural bearings of the region instead of uncritically consenting to bearings that beckon from down the road, over the pond, or across the border” (33–34). The cultural or corporate politics that make language contingent and unreliable, he argues further, are cleverly laid traps that reinforce already-overwhelming forces of self-hatred, and thus must be resisted. It is the joint task of artists and intellectual workers, he concludes, to open possibilities for re-examination of the intersections of selfhood and place, thereby ridding people of the prejudices they willingly hold against themselves (59).

Whalen, it is clear, opened the door wide for those of us who are embarking. It is not tribalism or adolescence that moves us to the New Brunswick work that we do, nor even our refined Maritime sense of a corrective, but rather the knowledge that our place is as worthy as any other of our critical attentions. To think or do otherwise, he reminds us, is to write another place’s history at the expense of our own.

Shortly after Whalen’s ground-breaking work, New Brunswick literary critics took up the call. David Creelman, for example, devoted the final pages of Setting in the East (216–17) to enumerating the many awakenings that attend the acceptance of place-based stewardship. One of the most apposite to the discussion of embarkation at hand is that of Ernest Buckler’s protagonist at the end of the magnificent novel The Mountain and the Valley. (I never tire of urging those who haven’t read the novel lately to re-read it — it is not only magnificently conceived but also an important orienting device for cultural workers.)

Though we know that Buckler’s protagonist David Canaan will die atop the mountain he long aspires to climb, the powerful lesson of the novel, and that which emancipates him (and, I think, us) is his final understanding of what must be done. Here are his words: “I will tell it, he thought rushingly: that is the answer.… I will put it down … telling these things exactly” (292). David does precisely, then, what another recent critic, Danielle Fuller, says “textual communities” like ours must do: we must write of “the everyday” as “an epistemological project” to identify and validate the “unarticulated stories and knowledges” around us (8). To do otherwise, agreed our late friend Herb Wyile, was merely to replicate the “austere bookkeeper’s world of neo-liberal economics” (240), thereby denying the political reality of history and each region’s unique response to federation and to personal truth.

It took the better part of a career for Canadian critical icon Northrop Frye to come around to this position, which he came to call the practice of “strategic localism.” To treat locality as symbol and trope, he said, even to use it as political wedge, was evidence of a culture’s maturity—not the adolescent phase it was for Brown and Smith, but, rather, key to Canada’s experiment with pluralism. “The more specific the setting of literature [or culture],” Frye wrote, “the more universal its communicating power” (“The Teacher” 7). If Canada was to speak to the world, then, it could only do so through the broken, incongruous, and sometimes unflattering voices of the Davids and the Sagouines. To do otherwise was, I repeat, to be coopted to doing the cultural work of others, writing their histories at the expense of our own.

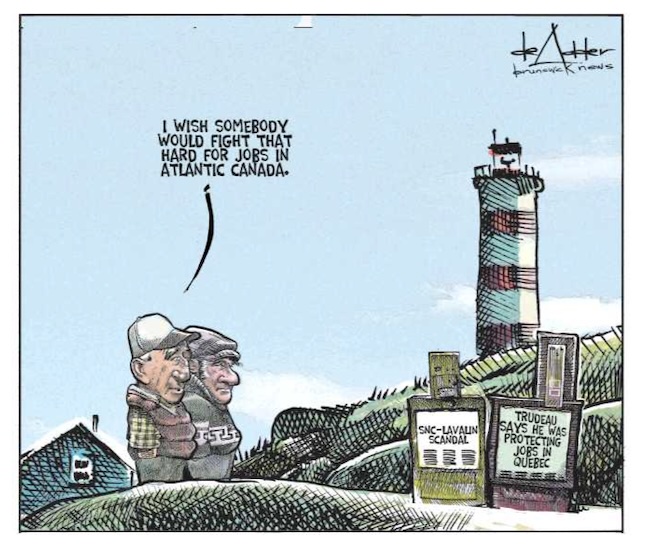

In New Brunswick, that understanding was rather crudely dramatized by editor Kent Thompson, who placed a carefully worded sticker on the winter 1974 issue of The Fiddlehead magazine. That issue was the journal’s hundredth, which Thompson had agreed to guest-edit. The sticker read “Take that, Toronto!,” a statement meant to celebrate The Fiddlehead’s longevity in New Brunswick and to challenge Toronto’s authority as the abstracted, overarching synecdoche for Canada. [Figure 3.] Whether Toronto deserved such a designation, or whether challenging it would bestir and galvanize local emotions, did not matter to Thompson. What mattered was how the provocation might upset assumptions about where and why culture happens. For Thompson, Whalen, McKay, and, I would argue, today’s Energy East dreamers, such decouplings are important points of incubation — and the more decouplings (and the wider their distribution, implied Frye), the more internal resources a population has. I take a recent political cartoon from Michael de Adder as updating what Kent Thompson did forty-five years ago. [Figure 4.]

How, then, do we proceed? How do we oppose old forms of representation and arrive “at new mythologies, [and] fresh indicators” (McKay 153) while working within an age of calculated and practised suspicion? We formulate, said Whalen, “a new faith in home” that, in accepting the demands of the work at our feet, and the trees and rivers at eye level, also pushes against the social and disciplinary tropes that consider such work nativist or out of the mainstream.

Those tropes were on full display during the question period after my talk when two colleagues pointed out limitations in the directions my work had taken. One colleague pointed to gaps in coverage that she perceived in the work; another asked about New Brunswick’s imprint in the world beyond its borders. Neither was being quarrelsome, but neither could conceive of the idea of a sovereign New Brunswick, a New Brunswick that did not have to be measured against a wider world or fall in line with what that larger world considers au courant in the discipline. In that regard, we in English New Brunswick still have much to learn from our Acadian neighbours, who have followed Seamus Heaney’s advice “not [to) displace our love and trust in the good of the indigenous” (460). As Acadian artists and intellectuals remind us, when we lose faith in the local, forgetting that it places its own signatures on how and why we do our work, we have been fully and irreversibly assimilated.

Embarkations

With the little space I have remaining, I will very briefly explain the rationale associated with a few of my own embarkations, each of which has deployed the strategies of localism described above.

I began ten years ago by constructing a New Brunswick Literary Encyclopedia, a digital project chosen because it was ideally suited to the energies of undergraduate and graduate students. I literally built the resource inside my classes, telling students that they could write conventional essays that had a half-life of a few hours and an audience of one, or that they could actually contribute meaningfully to knowledge production. Many of the better students saw the opportunity, working closely with me to shape entries that became peer-reviewed contributions to the discipline. On the strength of those contributions, many students got into professional or graduate programs—and all learned something valuable about writing for public audiences and turning their abstract though insistent feelings for place into something meaningful and transferrable. Now at more than 225 entries, the encyclopedia was getting a phenomenal 10,000 visits per month before domain changes in late 2019 necessitated its move to UNB’s more stable digital platform (that migration is now complete). As importantly, the encyclopedia has become a meeting place for scholars and students studying Canadian literature. I routinely get fifteen to twenty inquiries a week from scholars around the world who are working in the area. Student involvement was one of the most important aspects of that project because building a critical mass of young cultural workers was necessary for the larger vision of my work. My students who are now teachers use the encyclopedia’s resources in their classrooms across the region, thus further embedding the idea that a literature worth our attention does in fact exist in New Brunswick.

The 2017 New Brunswick Literature Curriculum in English spun out of that first project. Following the guidelines of the Atlantic Canada English Language Arts Curriculum, our province-specific version is a 750-page New Brunswick curriculum that covers the major periods and figures in the province’s literature. Designed for students and teachers at postsecondary levels, and for general readers interested in sampling New Brunswick literature, it has found its way into public schools in the province and is being touted as a model of future curricular development by current Minister of Education, Dominic Carty. The digital nature of the resource makes it easily accessible, completely self-paced, and, as I told Minister Carty, an example of the kind of bridge that can be built between universities and the larger publics that we serve. In this era of austerities of various sorts, our governments are especially receptive to this kind of collaboration, the NB Curriculum having been costed out at over $650,000 had the province gone to outside consultants to develop it. (I gave it to the province for free as a “Canada 150” gift.)

Finally, the same vision governed the development of the Journal of New Brunswick Studies/Revue d’études sur le Nouveau-Brunswick, a bilingual, multidisciplinary journal that provides a forum for scholarly writing and commentary about the province, something that we desperately needed (and still do). Now going into its eleventh year, the journal has become an influential policy instrument in New Brunswick by addressing topical concerns such as rural development, resource extraction, health care, election reform, and a host of other issues. The journal, moreover, has representation on its editorial and advisory boards from each of the province’s five universities, thus broadening the mandate of “strategic localism” to include related scholarly communities. My objective in that project was to mobilize a critical mass of New Brunswick researchers across the country while also narrowing the divide between Anglophone and Acadian scholars in the province so that each could find common ground and a larger readership.

I mention these projects not to celebrate my own modest achievements — in fact, these are all deeply collaborative ventures — but to illustrate how theories of “strategic localism” can be fashioned into the building blocks for the kind of cultural activism that Terry Whalen and Ian McKay encouraged. To the inevitable question of whether or not these tools have been successful in galvanizing provincial concern, my answer is that that is not my concern or any of my business. Others can judge success or failure.

What is important is that each of us, as scholars rooted in intellectual traditions, historical moments, and living, breathing places, take some real responsibility for the crossroads where we find ourselves. In my experience, standing at those crossroads takes courage, conviction, and stamina, for power always finds clever ways to mobilize against the outliers who proclaim loyalties against what is current and safe. And I am not speaking here of whom you might think. Resistance comes equally from inside as well as out, as those of us who must continually defend our courses and scholarship against colonials (and colonials in disguise) know.

What helped me as I thought about and shaped the trajectory of the last decade of my career was to reflect on how I could best serve the people and province from which I come. That meant severing ties with old supervisors, earlier habits, and self-reifying communities of like-minded scholars. It also meant challenging others, including students, to think differently about what we have been taught to dismiss and to venerate. It meant, in other words, revisiting the places (real and imagined) that are not always pleasant or affecting. And that is the greatest challenge in the work that many of us do, for returning to the spaces of the Sagouines and David Canaans can be emotionally uncomfortable. Yet, “if the economic heritage of the region is a tragic one,” wrote Whalen in anticipation of that feeling, “it is also possible to face its consequences squarely and to exorcise its ghosts” (58). Neo-provincialism, then, is not only an antidote to small-mindedness, but it is, more significantly, an avenue to addressing some of the traumas of our past, a conclusion that invites us as intellectual workers to explore aspects of “the folk” that are not especially comforting or uplifting. We can do this, said Whalen—indeed we should—while also celebrating the fealty to place that New Brunswick residents have always exhibited.

The “creative cultural opposition” (308) that McKay originally sought—that which turned from the view of contingent identity being negative and deficient to rooted identity being positive and productive—was in fact immediately in front of him, as it is in front of each of us today. It is manifest in Jocelyne Thompson’s work and your own, and in new and continuing fermentations that are springing up everywhere to contest the static forms of the “hegemonic ideology” of folk thinking (308). There is ample footing for all of us in alternate, post-folk histories—and opportunities, in our work, for our province to rise from its old status as the acted upon to become something more complex, dynamic, and positively endowed.

I will end with a few lines from New Brunswick poet Alfred G. Bailey to explain why that is—why an open-ended scholarship that is alive to the darkness as well as the light had always served him well. It is because, he wrote,

knowledge was in itself a good,

and would bear issue

in season, as did the earth around us

and keep us whole. (186)

He was writing of New Brunswick, as you are too. And in that endeavour, I wish you all well.

TONY TREMBLAY is Professor of English at St. Thomas University. He is founding editor of the Journal of New Brunswick Studies/Revue d’études sur le Nouveau-Brunswick and the New Brunswick Literary Encyclopedia. His recent work includes New Brunswick at the Crossroads: Literary Ferment and Social Change in the East (2017), the New Brunswick Literature Curriculum in English (2017), and The Fiddlehead Moment: Pioneering an Alternative Canadian Modernism in New Brunswick (2019).

Works Cited

de Adder, Michael. The [Fredericton] Daily Gleaner (5 March 2019): A8.

Bailey, A.G. “Reflections on a Hill Behind a Town.” Miramichi Lightning. Fredericton: Fiddlehead Poetry Books, 1981, 185–6.

Brown, E.K. On Canadian Poetry. 1943. Ottawa: Tecumseh Press, 1973.

Buckler, Ernest. The Mountain and the Valley. 1952. Toronto: McClelland & Stewart Ltd. (NCL), 1989.

Creelman, David. Setting in the East: Maritime Realist Fiction. Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2003.

Frye, Northrop. “The Teacher of Humanities in Twentieth-Century Canada.” Grad Post 2 (November 1978): 5–7.

Fuller, Danielle. Writing the Everyday: Women’s Textual Communities in Atlantic Canada. Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2004.

Heaney, Seamus. “Crediting Poetry: The Nobel Lecture, 1995.” Opened Ground: Poems 1966–1996. London: Faber & Faber, 1998, 445–67.

Maillet, Antonine. La Sagouine. 1971. Translated by Luis de Céspedes. Toronto: Simon & Pierre Publishing Co., 1979. [The image of la Sagouine is drawn by Patrick Bizier.]

McKay, Ian. The Quest of the Folk: Antimodernism and Cultural Selection in Twentieth-Century Nova Scotia. Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1994.

Smith, A.J.M. “From the Introduction to The Book of Canadian Poetry.” Towards a Canadian Literature: Essays, Editorials & Manifestos, vol. 2, 1940–1983, edited by Douglas M. Daymond and Leslie G. Monkman. Ottawa: Tecumseh Press, 1985, 336–40.

Thompson, Kent (guest editor). “Take that, Toronto!” The Fiddlehead 100 (Winter 1974): cover.

“Turn Around Troubled Fiscal Ship.” The [Fredericton] Daily Gleaner 22 September 2018: A10.

Whalen, Terry. “Atlantic Possibilities.” Essays on Canadian Writing 20 (Winter 1980/81): 32–60.

Wyile, Herb. Anne of Tim Hortons: Globalization and the Reshaping of Atlantic-Canadian Literature. Waterloo: Wilfrid Laurier University Press, 2011.